|

||||||||||||

|

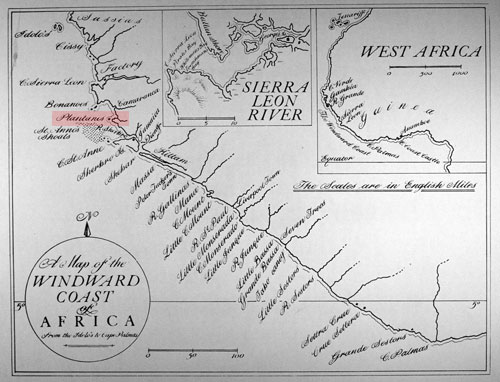

John Newton - Learning the Slave Trade 1745 - 1755 Ships involved in the Triangular Trade took out Sheffield goods, cloth, fire-arms and trinkets to barter with the chiefs and petty kings of West Africa for slaves; this 'cargo' was taken in turn by the notorious Middle Passage to the West Indies and/or the southern American colonies and sold; the ships returned home to Liverpool, Bristol and London with their holds full of rum or sugar or tobacco. A fortune could be made by captains and mates provided they survived the tropical fevers for long enough. For six months Newton remained on board, sailing from river mouth to river mouth collecting slaves from the 'factories' or warehouses on the coast where they had been brought from the interior. On board the ship was its part-owner, a Mr. Clow. Just before the ship was due to sail for the Americas the captain died and Newton took the opportunity to ask Clow, who was to land and continue trading, if he could join his service. Clow agreed. Clow took Newton to the largest of three islands, known as the Plantains at the mouth of the Sierra Leone River. Here Clow was to establish a new factory. When the factory had been made habitable Clow left Newton in charge while he left to fetch his 'wife'. This highborn African had the name P.I. and it was through her influence that Clow had prospered. She was an extremely important person and she expected to be the mistress of the island. Clow had planned to take Newton up the coast to trade but Newton fell sick with a fever. Newton had somehow fallen out with Princess P.I. and while Clow was away she had him moved out of his comfortable hut into an empty slave shelter and his rations cut to a handful of boiled rice. Half-starved Newton relied on roots pulled up and eaten raw and occasionally on food brought by African slaves.

On Clow's return Newton complained about his treatment but he was not believed. Newton accompanied his master on his second trip, where things went from bad to worse. Another trader accused him of cheating Clow and this was believed 'I was condemned without evidence. From that time he likewise used me very hardly; whenever he left the vessel I was locked upon the deck, with a pint of rice for my day's allowance.' ('Authentic Narrative'). He supplemented his diet by fishing using the entrails of fowls, which were being prepared for his master, as bait. Sometimes he was lucky but many times he went hungry. Nor were the physical conditions easy: here is Newton's own description of this time.

On returning to Plantain Island the regime carried on as before. Newton's one consolation was a book, the only book he had - Barrow's 'Euclid'. He used to go to remote parts of the island to draw out diagrams in the sand.

During the next twelve months Newton wrote to his father asking for help and Captain Newton applied again to Joseph Manesty, 'who gave orders accordingly to a captain of his who was then fitting out for Gambia and Sierra Leone' (Richard Cecil's 'Life of Newton'). Meanwhile conditions had improved for young Newton. He had been given permission by Clow to live and work for another trader, a Mr. Williams, who treated him decently. Soon Newton was involved in the management of the business and he gained Williams's approval. Things were looking up and Newton began to enjoy the life, becoming more involved with native customs: to use a phrase current at the time Newton 'was growing black'. Joan McKillop References

|

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||