Rushes from the rivers of this country have been made use of since very early times. Long before carpets were introduced, rushes were strewn on the floors of the dwelling places of rich & poor. All floors were nothing but earth or rubble whether in cottage, inn or castle and rushes were reasonably warm to the tread. In the Middle Ages whole villages used to turn out to harvest rushes, which, as they were scattered on the floor would be scented with sweet herbs. In course of time as the rushes grew sour, they would be swept up and replaced. By the time the Tudors were on the throne carpets had been introduced and were fashionable among the rich. But for the greater majority of people rushes were still the main floor covering, but it now became customary to plait them together in neat coils and then sew those coils into mats. As only the best and longest rushes lent themselves to this process rush plaiting became restricted to those areas where crops were suitable and plentiful. These were mainly to be found in East Anglia and the Fens and rush plaiting became an important industry of the Norfolk Broads and valleys of the rivers Ouse, Nene, Avon and Lovat.

In those days it was essentially a cottage craft worked as a family unit. Women and girls would plait daily in their back gardens, watched often by their children, who must learn the craft, while the man's part of the industry was to attend to the growing and harvesting. The family obtained what orders it could and made their profits, though usually small. The man of the family doubtless would have had some other form of employment, most likely farming.

Today rush plaiting is carried out under far more up-to-date conditions but of course the plaiters are considerably less in number. The finished article is marketed in the manner of present day and the craftsmen and women earn a reasonable living. Work is carried out in up-to-date workshops but the character of the work is much the same as ever it was: the men attend to the harvesting and growing and the girls the actual plaiting and sewing up.

The rushes are cultivated in special beds and cropped every other year. Experience has shown that the perfect specimens are obtained only in the second year of growth by which time the rushes will be 8 or 10 feet out of the water. If left to grow for a longer period they will become brittle and not lend themselves to efficient or easy plaiting. Harvesting takes place in June or July and the aim is to cut as close to the root as possible and so obtain the "butt end" the strongest section of the rush. Sickles or scythes are used, fastened to long poles 8 feet in length and it is often necessary to wade waist deep into the water. When cut the rushes are washed free of weeds and mud and spread out to drain off. They are then bunched together in "stookes" to weather and here great care must be taken to protect them from the sun, otherwise their colour will fade. After about 10 days the crop is taken to the workshops. Barges are frequently used for transport, where conditions lend themselves. These will be drawn by horses ( and sometimes men, in the past) walking along the river bank. In the workshops the rushes are sorted and graded and finally dried in an airy place. Before use they must be made wet again, but they must be stored dry to prevent rotting.

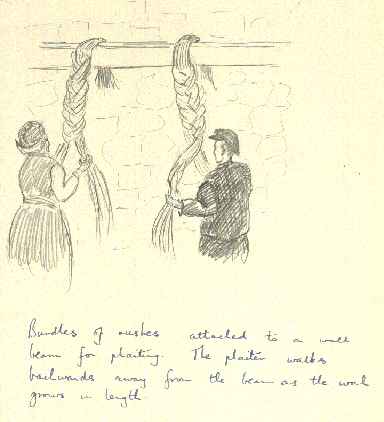

The plaiting itself is carried out with the aid of wall beam. A bundle of rushes is tied to the beam and the plaiter works and walks backwards as the plait grows. As the coil increases and will not keep taut it is wound round the beam and the plaiting continues. The operation of plaiting looks very simple but considerable skill is required to produce an even coil. New rushes must be inserted into the plait when necessary without showing in any way for often a coil of several yards must be worked. The coils for the body of a mat or carpet are mainly of 9 ply, while the borders are worked of a wider plait. The finished coils are handed over to other women for sewing up. This is done on a special table with a toothed edge to prevent slipping. The sewing must be done with great care. There must be even stitches and no puckering or the mat will not lie flat. A skilled girl can often plait 30 or 40 yards in a day, while a carpet of around 12 feet square would probably take a week to sew up.

Mats and carpets are not the only products of the industry. Log baskets and laundry baskets are also widely made whereas not so many years ago it was quite common to see any workman carrying his tools and meal in the 'utility' type rush bag. Often large areas of rush matting would be used as screens in country gardens and rushes were often plaited into toys, though more for pleasure than profit. The various types of bags and baskets usually required a different ply so it was necessary for a skilled plaiter to know all the different methods of plaiting. The workmen's bags were known as frails and were plaited in some districts and woven in others. When woven the work was done over a block to give the required shape. A box or flower pot or any firm object of suitable shape can be used. As there was often weakness in the handles of these old fashioned frails, webbing was often used and taken round underneath the basket for strength. Even a binding of webbing was not uncommon. When rushes alone were used for handles they would fray in a very short time and would need to be re-newed.

Sometimes the seats of chairs were made of rush plaiting. This needed even greater care and neatness and especially good sound rushes. English rushes were not popular for chair seating, a Dutch variety being preferred. It seems that the salt of tidal waters produces a fibrous quality in rushes which makes them last much longer than those grown in fresh water.

"Made in England", by Dorothy Hartley, says 'Rushes were used for chair seating, for bedding, for the shepherds shady hat, they were built into the plaster of walls, they were used to enwrap the soft mill cheese, to pleat and goffe fine linen veils. Bundles of rushes were flung into bags to make it possible for the pack horsesto flounder across, (ditches & boggy areas NA.); torches and other lights were made of rushes! Obviously the craftsmen and women of those days were far more ingenious in their use of the products of nature and occupied their leisure time more usefully than many of their modern counterparts.

References:

Rural Crafts, Norman Wymen, Oxford United Press 5/- Rural Crafts of England, K.S. Woods, Harrap. Made in England, Dorothy Hartley, Methuen 16/-

The article above is taken from: A fourth work from Doris Stephens, B4. SHS.- 20, 10, 2001