First Command 1750: The Duke of Argyll

|

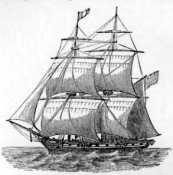

The Duke of Argyll was a Snow, which is a variation on a Brig.The full-rigged Brig is a vessel with two masts, fore and main, both of which are fully square-rigged. A Snow (shown here) is a brig with an auxiliary mast attached to the back of the mainmast for a fore-and-aft sail.

|

|

When Newton sailed as captain on the 'Duke of Argyll' in August 1750, he had charge of some 30 sailors. He was determined to set a good example, taking care to be abstemious in food and drink. As Richard Cecil writes:

I have heard Mr. Newton observe, that, as the commander of a slave-ship, he had a number of women under his absolute authority: and knowing the danger of his situation on that account, he resolved to abstain from flesh in his food, and to drink nothing stronger than water, during the voyage.

Was marriage to Polly was having an effect on his behaviour at sea? The implication is clear that on the previous voyage on a slave-ship his behaviour was not so moral. If this is the case it is hardly surprising. Apart from normal young male libido at work, crews were actively encouraged by the owners and captains to have sexual relations with the female slaves. The reason was simply the profit motive. Pregnant slaves would fetch a higher price at auction: two for the price of one. Particularly this was so if it were obvious that the child had been conceived at sea since a mulatto baby would fetch a higher price than a darker skinned one. Lighter skinned slaves were prized as house servants, which fetched higher prices than field hands.

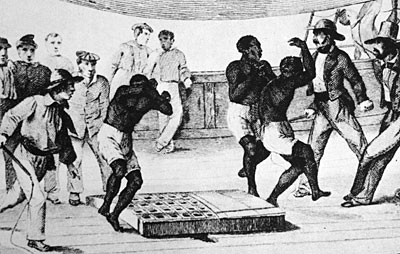

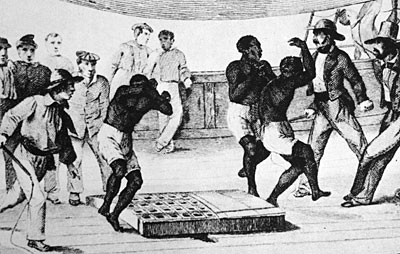

Slaves being "exercised" on deck

The voyage was not uneventful, some 20 slaves had managed to get free and it took until the next day to secure them. Newton punished them by using thumbscrews on the ringleaders. Despite this his treatment was, in the context of the period, humane. Below decks were cleansed regularly and the slaves also brought on deck to be washed.

He buried at sea only six slaves, a remarkable record. The middle passage ended in July 1751 when he anchored in Antigua, a British island in the West Indies. He returned to Liverpool in November of that year.

The Second Voyage as Captain and an Important New Acquaintance

He next sailed in a new ship, appropriately called 'The African' in July 1752.

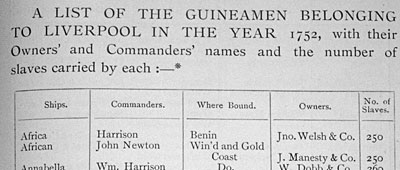

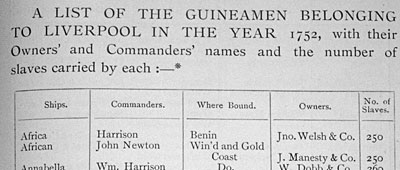

"The African" listed with its Commander, John Newton

"The African" listed with its Commander, John Newton

From "The Liverpool Privateers" by Gomer Williams, 1897

During his time in African waters he managed to put down an attempted mutiny by some members of the crew as well as an insurrection by the slaves - the crew 'was much menaced by our cargo.'

It was August 1753 when 'The African' returned to homeport and only six weeks later sailed again for West Africa. The trading was poor and Newton carried only 87 slaves to St Kitts (St. Christopher's) in the West Indies, instead of the usual 220. However the increased room below decks meant an increased survival rate and the entire voyage passed without a single death, amongst either crew or cargo.

It was while in St. Kitt's that Newton met someone who had a profound effect on him. Alexander Clunie was a sea captain who was not involved in the Triangular Trade. They soon became friends; Clunie was a Scot and belonged to the Independent chapel in Stepney, London. His minister was Samuel Brewer, a friend and pupil of Dr Jennings, who had been Elizabeth Newton's pastor at the Independent Meeting House at Wapping, where John had been baptised in July 1725. Both Brewer and Jennings had been friends with Isaac Watts (1674-1748), the famous hymn writer.

Under the influence of Clunie, Newton's understanding of his faith became more focused.

I was all ears and what was better, he not only informed my understanding but his discourses inflamed my heart.

For nearly a month the two met alternately on board each other's ship.

Although Newton had read and re-read the Bible and other religious books such as Hervey's 'Meditations' and Scougal's 'Life of God in the Soul of Man', meeting Clunie turned an intellectual exercise into a more outward expression of his faith. With encouragement Newton began to pray aloud. Clunie also gave him addresses of others from whom to seek further instruction. Newton lost no time and began, in June 1754, a series of letters to Dr David Jennings. He also kept in touch with Clunie; his letters between 1761 and 1770 were later published as 'The Christian Correspondent', in which Newton paid him this tribute:

Your conversation was much blessed to me at St. Kitt's, and the little knowledge I have of men and things took its first rise from thence.

The voyage back to England was uneventful apart from storms in the Western Approaches and when 'The African' docked in August 1754 Newton was unaware that he would never go to sea again.

Joan McKillop

March 05

(END of 'Childhood and Early years at Sea': three more sections to be added in due course)

References

- Newton, Rev. John: 'An Authentic Narrative', London 1764

- Cecil, Rev. Richard: 'The Life of John Newton' edited by Marylynn Rouse, Rosshire Christian Focus 2000

- Pollock, John: 'Newton The Liberator', London Hodder & Stoughton 1981

|